Key information

Main city: Harare, Zimbabwe.

Scope: Sub-city level

Lead organisations: Zimbabwe SDI Alliance (Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation and Dialogue on Shelter Trust)

Timeframe: 2010 – 2015

Themes: Informal settlements; Energy; Health; Transport and mobility; Water and sanitation

Target population: Households: 480. Individuals: 2,050.

Finance invested to date: US$3.8 million (DZ Extension). Funding sources: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (main funder); community contributions; Harare City Council (exemption of approval fees, equipment, technical supervision); Selavip Foundation; SDI (additional funding, technical support); UK Department for International Development.

Approaches used in initiative design and implementation:

- Co-production.

- Densification.

- Incremental housing development.

- In situ informal settlement upgrading.

- Participatory housing design.

- Participatory planning.

Local Area: Dzivaresekwa Extension

Area type: Holding camp

Level 1 administrative unit: Mashonaland West Province

Level 2 administrative unit: Zvimba

Level 3 administrative unit: Dzivarasekwa

Initiative description

Background and context

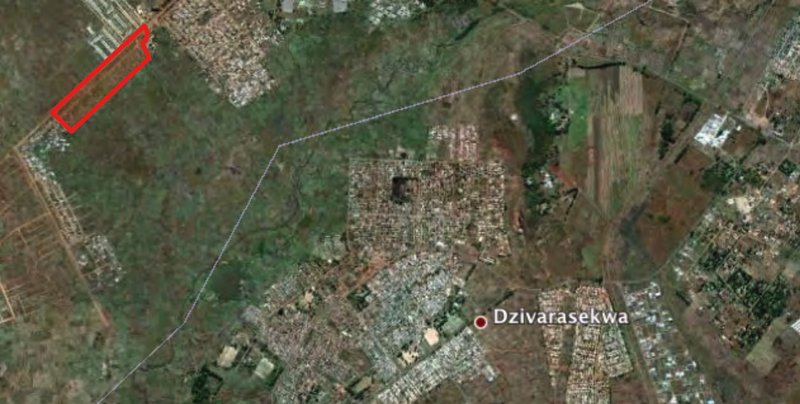

Dzivarasekwa Extension (or “DZ Extension”) is located 18km west of Harare. It was established as a “hidden” holding camp for informal settlement dwellers evicted from the Harare informal settlements of Epworth and Mbare before the 1991 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting. Initially, the informal settlement residents were relocated to Porta Farm and subsequently those who were “gainfully employed” (that is, had a formal job) in Harare were further relocated to DZ Extension.

DZ Extension is one of the two holding camps – the other being Hatcliffe Extension – where the Zimbabwe Homeless Peopleʼs Federation (ZHPF or federation) first came into existence in 1998, through establishing savings schemes. It sits on the fringes of Dzivarasekwa Main, which was established in the 1950s as a residential area for domestic workers employed in nearby formerly white-only areas. DZ Extension is home to 480 families, living in semi-permanent housing structures and lacking basic amenities such as roads, drainage, electricity and sewerage. DZ Extension was originally only served by communal toilets, and by protected and unprotected wells for water provision.

In 2007, the government of Zimbabwe allocated the state-owned land on which DZ Extension is located to the ZHPF. The federation is a community-based organisation made up of a network of savings schemes in low-income communities. The federation is supported in technical matters by Dialogue on Shelter Trust (DoST), an NGO. When the DZ Extension land was allocated to the federation, it was zoned as a high-density residential development.

In 2010, the Harare Slum Upgrading Programme (HSUP) was launched as a five-year project partnership of the federation, DoST and Harare City Council, with a US$5 million grant from the Gates Foundation. It is steered by a project management committee composed of representatives from the federation, DoST and staff drawn from Harare City Council’s various departments. As part of the wider HSUP, DZ Extension was chosen as a pilot for informal settlement upgrading; this decision was made taking into account the absence of partisan political contestation and federation ownership of land.

Summary of initiative

The aim of the project is in situ informal settlement upgrading, including the provision of bulk infrastructure. In 2010, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed among DoST, the federation and the Harare City Council to support collaboration at the city scale. Community members were involved in data collection, mapping and land inventories, planning and building houses, and upgrading of services. The data and mapping collected with the involvement of the community was linked with the city’s cadastral maps and development plans. Federation-linked savings groups organised the residents of the settlement for the upgrading project.

The federation wanted to use DZ Extension to demonstrate the viability of increased housing density in reducing the costs of building, land and services. With the help of a Harare City Council architects, Slum/Shack Dwellers International architect, and federation and DoST technical experts, three housing prototypes were developed, debated by community members during successive consultations and further revised to address the needs of the communities. After discussion, terrace and two-storey options were rejected by residents; semi-detached as an option was accepted.

Community members were involved in the building of prototype housing, trenching and laying of water and sewer pipes, and a community team of bricklayers and plumbers was trained. Savings group members selected those who would receive the housing, based on criteria of income and employment, mainly benefiting child-, elderly- and women-led households. The house building experiment was also used by Harare City Council to review housing regulations to allow the provision of low-income housing at scale.

The intervention provided tenure security, adequate water (solar-powered boreholes), a women-led waste management initiative and sanitation facilities (Eco-San toilets) and improved roads for more than 400 families, constructed 336 houses, and built an early childhood development centre and a community resource centre.

A learning platform was established to share the experience with other local authorities (Bulawayo, Kadoma, Kariba, Masvingo and Epworth) and the pilot project was scaled out to other settlements in Harare.

To ensure financial sustainability and extend the intervention to other informal settlements, the Harare Slum Upgrading Finance Facility (HSUFF) was established with the Harare City Council, with a financial contribution from the Harare City Council, the federation (via SDI) and DoST totalling USD 200,000 (SDI provided USD 50,000, the federation USD 30,000 and Harare City Council USD 120,000).

The average cost of housing was USD 2,400 for a 24 m2 dwelling. Houses are single storey and mainly detached. House construction costs are met by household savings and loans from the Harare Slum Upgrading Finance Facility (HSUFF) and the Gungano Urban Poor Fund.

Target population, communities, constituents or "beneficiaries"

Around 2,050 residents (480 families) received secure tenure, adequate water and sanitation facilities and improved roads. And 336 homes were built (1,344 people housed).

ACRC themes

The following ACRC domains are relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

- Informal settlements (primary domain)

- Housing

- Land and connectivity

The intervention primarily overlaps with ACRCʼs informal settlement domain, since it involves enhancing tenure security and improving housing, services and infrastructure of a settlement without the need for relocation or eviction and with the active involvement of the community.

The intervention also strongly overlaps with ACRCʼs housing domain, since it has improved the housing conditions and access to services and amenities of hundreds of low-income residents. Particularly, the following all strongly align the intervention with the housing domain: involvement of communities in the design process of culturally acceptable housing; incremental housing development; housing finance modality; and capacity building of communities in housing construction.

The intervention also overlaps with ACRCʼs land and connectivity domain, since it ensured residents’ tenure security and involved the provision of roads and other services.

The following ACRC crosscutting themes are also relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

Gender

The intervention has also an implication for ACRCʼs gender crosscutting theme by prioritising female-headed households, along with elderly and child-led households, in the allocation of housing. Additionally, women-led savings schemes of the Zimbabwe Homeless Peopleʼs Federation empower women in the area financially and equip them with collective agency to actively engage in the social affairs of the area. It is these savings groups which initiated the local authorities’ engagement in upgrading intervention. Additionally, 30 women were trained in solid waste management.

Finance

The intervention corresponds to ACRCʼs urban finance crosscutting theme, especially its low-income housing finance modality. The intervention created an arrangement for low-income households, which cannot access formal mortgages, to receive a housing loan. Additionally, the development of HSUFF (within the Harare City Council) was crucial for the financial sustainability of the intervention. As of 2019, HSUFF and the Gungano Urban Poor Fund (which had been established by the federation in 1999) have between them allocated loans for 550 DZ Extension households for income generation, water and sanitation, housing and land acquisition.

Climate change

The intervention also has an implication in terms of the ACRC climate change crosscutting theme. The introduction of solar-powered boreholes, public solar lighting and solar lights for households makes a contribution in reducing CO2 emissions (climate change mitigation). In addition, of the 30 women trained in solid waste management, some are engaged in recycling businesses. Furthermore, the introduction of eco-sanitation toilets enabled households to move onsite before the sewers were installed and temporarily reduced water consumption. Moreover, some efforts towards densification with semi-detached housing design have reduced costs and ecological footprint.

What has been learnt?

Effectiveness/success

Evaluation of the intervention has focused on:

- Quantitative indicators – number of houses constructed, toilets improved, water points installed

- Qualitative indicators – improved relations, partnerships and recognition by authorities of pro-poor models of housing construction and informal settlement upgrading.

The effectiveness of the intervention is aligned with the five preconditions that ACRC has identified as a catalyst for urban reform in its theory of change. These are: organised citizens; reform coalition; politically informed and co-produced project design; enhanced state capacity; and elite commitment.

- Organised citizens. This was a key precondition for the success of the intervention. The intervention was possible because informal settlement residents in Zimbabwe organised themselves into savings groups and federated at city and national scales. Their collective agency, with technical support from DoST, allowed the federation to receive the DZ Extension land, partner with authorities and other development partners, and mobilise DZ Extension residents for upgrading.

- Reform coalition. Building a partnership was a key to the effectiveness of the intervention. The success of the intervention lies in the partnership between Harare City Council, the federation of informal settlement residents (ZHPF), an NGO providing technical support (DoST), development partners (BMGF, DFID and Selavip Foundation) and the transnational SDI network. The involvement of the Harare City Council was not only crucial in the effectiveness of the project but also in scaling the intervention, through regulatory reform and allocation of USD 120,000 funding into HSUFF.

- Politically informed and co-produced project design. Politically informed evidence and co-produced project design was also vital for the success of the project. The intervention pragmatically selected DZ Extension as a pilot project, considering the minimal political risk and federation ownership of the land. Starting with a relatively simpler intervention and venturing onto more complex and politically contested interventions is an effective practical approach. In addition, the community-led enumeration (household survey), mapping and land inventory, which were interlinked with the cityʼs cadastre and development plans, demonstrated the challenges and assets of the settlement. The intervention also co-produced housing typologies in consultation with the communities. Promoters of the intervention used the process to convince Harare council to adopt a report on the review of housing regulation.

- Enhanced state capacity. Enhanced state capacity, in the form of working with communities and their organisations, and experimenting with new approaches to deal with informality, was critical for the success of the intervention.

- Elite commitment. Political commitment by elites was a key factor for the effectiveness of the intervention. The then Minister of Local Government signed an MOU with Dialogue on Shelter Trust and the federation, which paved the way for the the DZ Extension land allocation. Then the allocation of DZ Extension land to the federation by the government of Zimbabwe facilitated the in situ upgrading. Subseguently, an MoU was signed with the City of Harare which resulted in the establishment of the Harare Slum Upgrading Finance Facility. There were also instances when the local councillor from the political party Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) established good relations with the local DZ Extension Federation, supporting them around local needs, for instance, engaging City of Harare district officials to expedite house plan approvals. Although, some politicians also saw an opportunity to use the upgrading initiative as a platform to advance their own political ambitions. Most importantly, the active involvement of the Harare City Council in the implementation of the intervention, adoption of housing regulation reform recommendations and allocation of funds for the sustainability of the intervention was crucial for the effectiveness of the intervention.

The intervention is effective in terms of:

- Changing the attitude and mindsets of authorities, by demonstrating the viability of community-led in situ upgrading in partnership with city authorities.

- Developing a informal settlement upgrading model, which integrates housing, infrastructure, green energy solutions, environmental management and community development, with an aim of scaling the intervention.

- Improving tenure security, access to services for low-income people and making their settlement an integral part of the city.

- Building the capacity of residents and creating potential future income sources through supporting them to acquire construction skills.

- Forging and deepening enduring ties between DZ Extension Federation and City of Harare officials

Understanding limitations

Mistrust between communities and local authorities was a challenge which was addressed by successive exchanges, the establishment of joint project management committee and by signing a memorandum of understanding that provided a framework for the partnership. However, staff changes in Harare City Council have been a further limitation, making trust-building harder.

Reluctance among the DZ Extension community to accept the densification strategy was a further challenge, which was addressed by successive meetings with the community on housing typologies and multiple revisions of the housing designs to address their demands and needs.

Zimbabwe’s cash crisis has affected HSUFF, with high bank charges, difficulties receiving money via banks, and impacting households’ and businesses’ ability to make loan repayments. There have been efforts to address this by making loan repayment in cash. However, by 2019, HSUFF had been temporarily suspended, although it was still operating with a capital of around $200,000 USD (World Habitat, 2019).

Potential for scaling and replicating

DZ Extension was classified as an “upgrading laboratory” – ie, a learning platform for other local authorities through learning exchanges to inform policy and practice elsewhere.

Additionally, the University of Zimbabweʼs Rural and Urban Planning Department is involved with the project, creating research and first-hand learning opportunities for students. During the course of the DZ Extension project, field visits were also arranged for university students to have a practical experience of co-produced upgrading solutions.

Participating agencies

Further information

Further resources

References

Muchadenyika, D (2015). “Slum upgrading and inclusive municipal governance in Harare, Zimbabwe: New perspectives for the urban poor”. Habitat International 48: 1-10.

Shand, W (2018). “Making spaces for co-production: collaborative action for settlement upgrading in Harare, Zimbabwe”. Environment and Urbanization 30(2), 519-536.

Acknowledgements

The editors are grateful to staff at Dialogue on Shelter Trust, including Teurai Nyamangara, Patience Mudimu-Matsangaise and George Masimba, as well as to Daniela Cocco Beltrame at The University of Manchester, for reading earlier versions of this case study and providing additional detail and valuable comments.

Cite this case study as:

Weldeghebrael, E.H. (2024). “Dzivarasekwa Extension: in situ slum upgrading and affordable housing models”. ACRC Urban Reform Database Case Study. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester. Available online.