Key information

Main city: Harare, Zimbabwe.

Scope: City/town level

Lead organisations: Harare City Council ; Dialogue on Shelter Trust ; Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples’ Federation

Timeframe: 2010 – 2015

Themes: Informal settlements; Housing; Informality; Infrastructure; Planning and design; Urban regeneration

Main funder agencies: Bill and Melinda Gates foundation (USD 5 million); informal settlement communities (through community-based saving schemes); City of Harare (in kind contributions). Additional funding: Selavip Foundation; Slum Dwellers International; DFID.

Approaches used in initiative design and implementation:

- Co-governance and institutional partnerships.

- Community-led planning.

- Co-production.

- Incremental housing development.

- Participatory planning.

Initiative description

Background and context

Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe, has faced a prolonged urban housing crisis driven by rapid urbanisation, weak planning institutions and deepening poverty (Muchadenyika, 2015; Matamanda, 2020; Mutsindikwa, 2020). Almost a third of the city’s population lives in informal settlements characterised by insecure tenure, inadequate infrastructure and limited access to basic services (Muchadenyika, 2015). Decades of underinvestment, legalistic governance approaches and policies that criminalise informality have left low-income urban residents without access to services and security of tenure. These conditions are exacerbated by political tensions, underresourced local authorities and a history of top-down approaches that marginalised low-income communities from urban planning processes (Masimba and Walnycki, 2024).

In response to these challenges, the Harare Slum Upgrading Programme (HSUP) was launched as a multi-stakeholder initiative; part of the Global Programme for Inclusive Municipal Governance implemented in five African cities with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which aimed at strengthening municipal and community partnerships to tackle city challenges in inclusive ways (Muchadenyika, 2015). In Harare, the programme design aimed to demonstrate the viability of community-led, participatory and scalable approaches to in-situ informal settlement upgrading.

Throughout its implementation, HSUP had to navigate a complex political economy marked by fragmented governance and centralisation, politicisation of urban land allocation and weak institutional coordination. City of Harare (Harare City Council) authorities operate in a highly centralised system, where key urban functions such as land management and service delivery are influenced by central government ministries. This limits municipal autonomy and often causes delays, duplications and conflicting mandates, not least when local authorities try to implement reforms in informal settlements (Muchadenyika and Waiswa, 2018).

Since the introduction of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) in 2000, urban land allocation in Harare has become increasingly politicised, with informal settlements and housing cooperatives often used as instruments of political patronage, particularly during election periods. Settlements have sometimes been tolerated or evicted based on shifting political allegiances (Muchadenyika and Waiswa, 2018). Efforts at informal settlement regularisation or upgrading are therefore often politically sensitive, requiring careful alignment with national policy rhetoric, while building local legitimacy. Additionally, multiple agencies, including local authorities, central government agencies, NGOs and community groups, operate with poor coordination and unclear jurisdiction, making implementation slow and contested.

Summary of initiative

The 2010-2015 Harare Slum Upgrading Programme (HSUP) was a collaborative initiative co-led by Harare City Council, Zimbabwe Homeless People's Federation (ZHPF, a grassroots network) and Dialogue on Shelter Trust (DoS, ZHPF’s professional support NGO) in partnership with Slum Dwellers International network (SDI) and with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. HSUP sought to address systemic barriers to low-income housing by promoting participatory, inclusive and scalable solutions. It targeted low-income urban households living in informal settlements across Harare, who typically face tenure insecurity and lack access to basic urban services and formal housing finance.

Central to HSUP was the concept of co-production, whereby organised communities and local authorities collaborate in planning, implementing and managing urban improvements. The initiative focused on profiling and mapping informal settlements, strengthening tenure security, supporting incremental housing construction and introducing innovative finance mechanisms for households traditionally excluded from formal housing finance systems. Pilot projects combined community-driven design with technical support from authorities and NGOs, showcasing new models of urban development. Throughout the process, community members participated in data collection, land inventories, planning, house construction and service upgrading.

HSUP emerged in a context where informality was often criminalised, yet its implementation has reshaped relationships between informal settlement citizens and governing authorities in Harare, contributing to broader policy reform and inspiring replication in other Zimbabwean cities. The programme exemplified how urban transformation can happen at the neighbourhood level. It succeeded in institutionalising community participation in urban planning, challenging traditional bureaucratic norms, embedding new planning practices in Harare City Council, and encouraging a shift from top-down eviction-based approaches to collaborative upgrading models.

While it embedded new participatory planning practices within the City of Harare and inspired replication in other settlements, the durability of these changes has been mixed, with some governance structures fading after the project’s formal end in 2015. Nevertheless, HSUP remains an important demonstration of how mobilised citizens, reform coalitions and politically informed design can catalyse meaningful urban transformation, even in fragile governance contexts.

Initially designed as a five-year project (2010-2015), HSUP established mechanisms intended to promote sustainability and scaling beyond its pilot site. While its direct impact remains localised in Dzivarasekwa Extension, the programme’s participatory and co-governance approaches informed later upgrading efforts in other Harare settlements, such as Tafara, and inspired similar initiatives in cities including Masvingo (especially Mucheke and Victoria Ranch settlements), Kadoma (Cherrybank) and Bulawayo (Iminyela–Mabuthweni).

Data collection

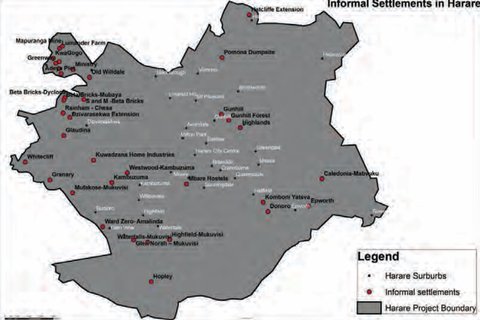

Implementation began with comprehensive citywide data collection, building a citywide understanding of informality, both to guide planning and to empower communities in negotiations with city authorities. This started with field visits to geographically locate informal settlements, followed by sensitisation, introducing communities to the profiling process and its objectives. Documentation captured each settlement’s history, tenure status, infrastructure and demographics. Settlement mapping captured spatial data to integrate with city maps and assess upgrading potential. And detailed household enumeration quantified the scale of informality. All information was compiled into narrative reports and spatial maps, and the process concluded with community feedback sessions to validate the data and encourage mobilisation, savings scheme formation and planning for upgrading.

Data collection was carried out by Harare City Council, DoS and ZHPF and led to production of the Harare Slums Profile Report (Dialogue on Shelter Trust et al., 2014), an upgrading profiling report which covered 60 informal settlements in and around Harare. Importantly, it enhanced the visibility of some settlements on which city authorities had little information. This also informed the next stage: selecting a pilot location for in-situ settlement upgrading, for which Dzivarasekwa (Dz) Extension was chosen, in place of alternative locations that were too politicised.

Upgrading pilot

A combination of factors – technical feasibility, social preparedness and political acceptability – made Dz Extension a strategic entry point for testing and showcasing HSUP’s upgrading model. Land was available that could be planned and regularised in piloting secure tenure and housing development. ZHPF’s active presence meant a strong community already mobilised and orientated towards coproduction efforts, saving collectively and engaging in grassroots planning activities. Earlier community-led data collection efforts provided a solid existing knowledge base to guide planning. The area was politically viable with a lower risk of elite or institutional resistance compared to more politically sensitive settlements, and therefore a practical choice for a pilot relying on community–municipal cooperation. And its size and location offered strong potential to showcase and demonstrate HSUP’s approaches of incremental housing, community-led design and city collaboration – establishing an influential model for replication in other informal settlements.

In Dz Extension, communities co-designed housing through participatory planning and exchange visits. Construction and infrastructure work was led by communities with technical support from DoS and Harare City Council. Construction began in 2011. Aspects of this approach have since been scaled and replicated in other Harare settlements, such as Mabvuku-Tafara, Stoneridge, Hatcliffe, Mbare, Hopley, Crowborough, Msasa, Jumbo and Glaudina (Dialogue on Shelter, 2025). The Dz pilot is described in detail in a separate ACRC urban reform case study (Weldeghebrael, 2024).

Finance innovation

Lessons from the Dz pilot identified challenges for low-income housing delivery, prompting stakeholders to reflect on and/or revise restrictive systems and regulations. HSUP had international funding and also leveraged community savings, establishing an innovative loan mechanism for low-income households typically excluded from formal finance systems. The Harare Slum Upgrading Finance Facility (HSUFF) was a co-created financing arrangement located within the city council’s structures. It was designed to support low-income urban residents excluded from formal financial systems, and provided access to credit for a variety of upgrading needs, including housing construction, land acquisition, water and sanitation and small businesses. Financial contributions were shared and the Harare City Council contributed USD 120,000 to capitalise HSUFF, while the alliance of DOS and ZHPF had the support of Slum Dwellers International to invest USD 80,000 (Masimba and Walnycki, 2024). HSUFF became operational around 2013-2014, a key milestone being the successful allocation of loans to 550 households in DzExtension by 2019.

HSUFF was notable for its shared oversight and co-signatories from the city council, while the Federation groups sought to ensure transparency and accountability. Although HSUFF was located within the city’s institutional framework, community representatives played a key role in identifying priorities, vetting loan applications and monitoring repayment. The loans complemented the efforts of the ZHPF’s existing community-led Gungano Urban Poor Fund established in 1999. Federation members in Dz Extension could therefore benefit from grassroots savings initiatives, the Federation loan fund and the more formal finance provided by HSUFF.

While initially tied to HSUP’s contractual period, HSUFF has extended beyond the project and has inspired replication in Masvingo and Bulawayo. It demonstrated that communities can responsibly manage and repay loans, challenging common risk perceptions around lending to informal residents.

Programme co-management

HSUP was steered by a project management committee with representatives from ZHPF, DoS and relevant Harare City Council departments, creating a space for co-governance and shared decision making. This structure was significant in building trust, enabling transparent communication and ensuring that both community priorities and technical and municipal requirements were taken into consideration during planning and implementation. Working relationships under HSUP were collaborative and flexible, with the committee serving as a crucial experiment in participatory governance and financial co-management in a politically sensitive urban setting. The committee facilitated site visits, joint planning meetings and coordinated technical support, over time becoming a platform for negotiation and accountability. However, its effectiveness faded after HSUP’s contractual period concluded due to a lack of political commitment in the absence of external resources.

Overall, HSUP supported a shift in how informal settlement upgrading is approached in Harare, from a top-down model to one driven by data, community agency and collaborative governance. Not all plans (like a planned-for municipal slum upgrading unit) were fully realised. Nevertheless, the initiative has left a significant legacy in policy, practice and community empowerment.

ACRC themes

The following ACRC domains are relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

- Informal settlements (primary domain)

- Health, wellbeing and nutrition

- Housing

- Land and connectivity

- Neighbourhood and district economic development

Alignment with several ACRC domains reflects HSUP’s holistic approach to tackling the multidimensional challenges of informality while promoting inclusive urban development. The programme focused on improving living conditions in informal settlements and underserved urban areas through participatory in-situ upgrading, in particular co-production of low-cost, incremental housing as well as efforts to secure tenure and integrate informal settlements into formal city planning. This led to improvements in water, sanitation and waste management, as well as supporting income-generating activities such as recycling and artisan training.

The following ACRC crosscutting themes are also relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

Gender

HSUP implementation capitalised on ZHPF’s core network of women-led saving schemes. These promote women’s empowerment, prioritise female-, child- and elderly-headed households in accessing and building decent affordable housing, and equip women with the financial muscle to improve housing conditions and the collective agency to actively engage in the social affairs of their area (Weldeghebrael, 2024).

Finance

Zimbabwe’s macroeconomic crisis creates challenges for sustained external financing. National budget support for local authorities also remains very limited. HSUP therefore had to demonstrate innovative and blended financing mechanisms to move forward with its focus on pro-poor financing options, in particular HSUFF, which was established as a co-governed financial mechanism within the HSUP framework. And while HSUFF encountered challenges due to this very difficult economic operating environment, it represented a significant step towards institutionalising co-resourced and revolving finance for low-income housing and services. The sustainability of the fund could be achieved through mechanisms designed to ensure transparency among all participating institutions. By implementing these measures, the fund minimises the risk of misuse and corruption, as it incorporates robust accountability safeguards. The facility’s design and early operations provided valuable lessons on how collaborative urban financing tools can enhance accountability, trust and resilience in contexts of fiscal fragility (Masimba and Walnycki, 2024).

Climate change

Climate change impacts can be addressed through improved housing and informal settlement upgrading. HSUP implementation employed environmentally friendly solutions, such as EcoSan toilets, solar-powered boreholes and solar lighting in public places and for households. Residents were capacitated to plant trees and lawns to mitigate wind storms, flooding and dust in homes. Gully reclamation in Dz Extension also helped to curb effects of flooding.

What has been learnt?

Effectiveness/success

How does the initiative define success?

For DoS and ZHPF, success was understood in terms of the ability of communities to influence urban planning, acquire tenure security and access infrastructure through participatory means. For the municipal partner, Harare City Council, it meant improved service delivery and policy credibility. For funders, success meant innovation and replicability.

Community reflections (quotes from Schermbrucker, 2013)

Among the Harare informal settlement residents involved, including ZHPF members and community leaders, understanding of success was deeply rooted in both HSUP’s process and outcomes, and goes beyond simply constructing houses to building systems that allow marginalised urban communities to shape their own futures. Defining markers of success included:

- Community empowerment and inclusion in decision making processes.

- Collaborative governance, with broad mutual accountability grounded in trust, shared power and responsibility.

- Financial inclusion and access to flexible finance.

- Community control over loan processes.

- Holistic and incremental upgrading.

- Establishing systems that reach scale and improve lives.

This is captured in a quote from ZHPF community leader, Catherine Sekai Chiremba, during HSUP negotiations with Harare City Council: “We want to be together with the city, not just us accountable to the city. So we can learn from each other and that people are encouraged to pay back loans that can then revolve. We want to work together to disburse the loans.”

Success was understood in terms of communities’ ability to influence how finance is structured and used; not just receiving loans but ensuring that funds are accessible, realistic and aligned with people’s real needs. Experience managing the Gungano Urban Poor Fund shaped preferences for staged, collective loans to reach more people and foster a shared commitment to repayment, an approach seen as more sustainable and impactful than individual lending.

Success was also tied to what the finance supports, pushing back against narrow definitions of housing finance to argue for a more holistic, incremental and demand-responsive logic that includes services, land and infrastructure. This framing reflects the lived realities of informal settlement dwellers and the need for context-sensitive, community-controlled approaches to development.

“Housing is not in isolation, it is complex. We look at land, water, sanitation and shelter. All of these four items contribute to housing” (Shadreck,Tondori, ZHPF).

“Housing cannot be the greatest priority because you cannot build a house without land and services. We want to address things incrementally and not start at the end” (Davious, ZHPF community leader).

These understandings of success under HSUP incorporate all four of the preconditions for catalysing urban reform captured in ACRC’s conceptual framework.

- Mobilised citizens were central to the initiative, with ZHPF leading community-driven planning, savings and construction efforts. Grassroots data and local knowledge influenced planning decisions and unlocked land for housing.

- The initiative was politically informed and co-produced, responding to Harare’s fragmented governance context. HSUP fostered robust formal and informal reform coalitions, notably between DoS/ZHPF and Harare City Council. These partnerships were instrumental in shaping inclusive planning processes and co-governance structures like the project management committee.

- The programme contributed to building both short- and long-term state capacity, through technical support, data-sharing and creating financial instruments within city structures.

- Clear political commitment from municipal elites was demonstrated by the adoption of regulatory reforms, specifically the Informal Settlement Upgrading Protocol intended to guide the city of Harare in upgrading informal settlements within its jurisdiction, as well as continued collaboration with informal settlement communities.

- By navigating political settlements and establishing enduring alliances, HSUP exemplifies a city-of-systems approach, addressing interconnected challenges across housing, land, finance and service delivery, while embedding reform in both community and institutional practices.

How successful has the initiative been?

Here, assessment of success draws primarily on community feedback gathered in DoS/ZHPF-led reflection meetings and learning platforms, documentation of improved living conditions in particular settlements, and visible shifts in municipal practice. The tangible and intangible developments observed across social, institutional, environmental and physical fronts as a result of the HSUP reflect both direct outcomes and broader shifts in Harare in attitudes and systems related to informal settlements.

Viewed through the lenses of its main stakeholders – informal settlement residents – HSUP has been broadly successful. Internal project reviews and evaluations (in particular, project management committee reflections and HSUP learning reports) highlight improved governance, infrastructure and citizen agency. The initiative achieved meaningful partnerships, community participation and capacity-building, improved housing and tenure security, and created scalable upgrading models. Communities were able to gain tenure security, influence planning processes and access improved services. Participatory planning, data-driven relocation and self-built housing using collective savings mark these as strong outcomes.

HSUP opened political space for low-income communities to engage city authorities directly and influence policy and financial structures. It also validated community-led finance and planning models previously dismissed as informal or unreliable. The programme demonstrated that, when given trust and flexibility, communities can manage loans, plan settlements and build incrementally. And it shifted the city’s approach (at least during project implementation) from a top-down, service delivery model to one rooted in co-production and mutual accountability.

Physical improvements

Some residents, like those living in Dz Extension, transitioned to more durable housing structures, improving safety and resilience. Incremental development and self-building became more widespread, allowing low-income households to build affordably over time. Solar lighting reduced fire hazards and improved nighttime safety. Greening helped control dust and flooding as well as improve air quality.

Tenure security

“The adoption of participatory slum upgrading as a strategy for tackling informal settlements under the Harare Slum Upgrading Programme created a real opportunity to secure tenure for the majority of slum dwellers” (Matamanda et al., 2020: 11). After the Ministry of Local Government approved a participatory upgrading layout plan (ibid), 408 households in Dz Extension and over 7,000 in Epworth Ward 7 were issued tenure security based on community-generated data and participatory planning (Muchadenyika and Waiswa, 2018).

Strengthened social capital

HSUP processes strengthened grassroots organisation. Communities formed savings groups, building brigades and cooperatives that led construction, savings and advocacy efforts. Joint building activities, savings groups and governance forums fostered unity and reduced internal conflict. And ZHPF’s existing presence in settlements was enhanced as members gained skills in negotiation, construction, data collection and governance.

Access to housing finance and livelihood and economic outcomes

Through HSUFF, HSUP enhanced residents’ access to finance with loans for housing construction or livelihood improvements. Training for local artisans led to long-term employment, even in non-Federation areas, and involvement in waste recycling, solar energy sales and construction increased household incomes for those involved.

International recognition

In 2012, the then-ongoing HSUP was recognised by the UN-Habitat Scroll of Honour award to then Mayor of Harare, Muchadeyi Masunda. The global award recognised outstanding contributions to improving human settlements, highlighted the mayor’s leadership in collaborative urban governance, and acknowledged the HSUP partnership between Harare City Council, DoS and ZHPF.

Policy and planning influence at national and municipal levels

There has been influence on national and local planning, policy and practice. The participatory process adopted by HSUP gained credibility and influenced the 2021 National Human Settlements Policy, which reflected greater government recognition of urban informality and indicated shifting state attitudes – from traditional approaches of eviction, demolition and displacement towards more pro-poor, people-centred approaches of upgrading and regularisation. Continued application and scaling of HSUP practices in other cities further reinforces perceptions of success across stakeholder groups (see Scaling and replication section, below).

At the municipal level, HSUP’s influence on improved service delivery models, strengthened institutional relationships and enhanced policy legitimacy is evident in Harare City Council’s independent replication of aspects of HSUP in other informal settlements, such as Mabvuku-Tafara, Stoneridge, Hatcliffe, Mbare, Hopley, Crowborough, Msasa, Jumbo and Glaudina. HSUP established direct lines of communication and cooperation between informal settlement dwellers and local government officials through one-stop shops, site visits and Harare City Council contact persons, leading to improved collaboration. Creation of governance structures, such as the project management committee, enabled co-production and brought communities into formal decision making. At the same time, HSUP brought about changes in urban planning as Harare City Council gained a better understanding of the link between informal settlement growth and broader urban dynamics through informal settlement profiling, leading to a push for more coordinated, long-term strategies for inclusive city-growth (Matamanda et al., 2020). Community-led data use also improved, with communities using enumeration data to advocate for services, plan upgrades and resist evictions.

Understanding limitations

As a result of HSUP, there has been a shift in the way in which Harare City Council interacts with informal settlement dwellers. However, this shift remains fragile, inconsistent and highly contingent on enabling conditions – political, economic and institutional. It represents an important foundation, but sustained progress requires institutionalising these practices, scaling up financing and building political consensus across all government tiers.

Many of HSUP’s challenges reflect deeper structural constraints in Harare. The broader political economy of urban land governance – characterised by politicised land allocation, limited devolution and constrained municipal autonomy – posed a persistent obstacle to scaling up. While strong partnerships were built at the municipal level (with Harare City Council), the absence of national-level buy-in and the dominance of centralised authority limited HSUP’s potential to transform citywide systems.

Staff turnover at Harare City Council affected implementation because new officials lacked institutional memory, affecting continuity. Incomplete institutionalisation was another limitation and failure to establish a planned dedicated Slum Upgrading Unit meant the absence of a permanent municipal structure to sustain momentum. Weak post-project continuity is a related limitation: following the dissolution of governance structures after HSUP’s formal end in 2016, some settlements in the project, such as Rainham Park, were subsequently threatened with eviction and displacement.

Funding and financial management constraints included low repayment rates on some household loans, the effect of inflation and currency changes on HSUFF’s operating capital, and lack of flexibility. Internal DoS/ZHPF reflections highlight that requirements for joint signatories with Harare City Council at times created delays in disbursing funds.

While the intention was to streamline or standardise processes, centralising procurement using agents – rather than allowing communities to purchase materials directly or locally – at times led to cost inefficiencies. Agents’ service fees and mark-ups made materials more expensive than if communities had sourced them directly, and limited their ability to select materials based on local context, price or safety. As a result, materials like inverted box rib metal roofing sheets were supplied despite their safety issues, such as risks of electric shocks due to poor insulation.

There has also been government reluctance to support and adopt some of the alternative service delivery solutions demonstrated by HSUP, particularly sanitation. This hindered the scaling up of some of the cost-effective, context-appropriate innovations that were identified. Despite progress by DoS and ZHPF in promoting alternative, dry sanitation technologies, Harare City Council’s urban standards continue to prioritise traditional wet systems, viewing dry options as inadequate and primitive (Matamanda et al., 2020).

Lead agencies responded to challenges with adaptive learning, leveraging data, community mobilisation and international recognition to maintain visibility and legitimacy. The DoS-ZHPF alliance strengthened direct relationships with city officials, utilising enumeration data to advocate for land access and service delivery, and promoting income-generating projects to support sustainability.

Potential for scaling and replicating

HSUP’s significant potential for replication is evident in the City of Harare's own internal efforts at informal settlement documentation and regularisation. By 2023, Harare City Council had approved the regularisation of “many” originally unplanned informal settlements that could be upgraded to meet minimum planning and servicing requirements (Harare City Council, 2023), had established a regularisation steering committee together with a regularisation task force responsible for city-level coordination and oversight, and had developed a regularisation checklist and standard operating procedure.

Beyond Harare, the cities of Masvingo, Kariba, Bulawayo and Kadoma have adopted various practices introduced by HSUP, such as decentralised EcoSan sanitation. Learning exchanges between cities and urban areas such as Bulawayo, Kadoma, Kariba, and Epworth have supported learning and adoption of informal settlement upgrading and regularisation programmes. Co-governed funding models are also being expanded to other municipalities. These represent an inclusive, innovative solution to urban poverty and service delivery challenges, and a practical pathway to build city–community partnerships, institutionalise participatory governance and channel funding towards locally determined priorities.

Opportunities for scaling up and replication are leveraged by the civil society partnerships strengthened by HSUP and bolstered by the presence of peer learning platforms and forums such as the Urban Informality Forum (UIF), whose formation was influenced by HSUP.

Institutional challenges to scaling HSUP include the absence of a dedicated government unit to champion replication and lack of formal monitoring, evaluation and learning frameworks to guide upgrading and regularisation processes. Staff turnover and political risks also continue to disrupt implementation and continuity.

Key lessons

Below are a set of key lessons learned from HSUP drawn from DoS and ZHPF reflection meetings:

- Data drives inclusive, evidence-based planning. Comprehensive data from settlement profiling, mapping and enumeration played a crucial role in HSUP, enabling inclusive planning and advocacy.

- Community ownership drives project sustainability. Mobilising communities was essential in stirring savings initiatives, housing construction, advocacy, and for ensuring relevance and accountability. Project implementers should prioritise participatory planning, involving residents from the onset of projects to build legitimacy.

- Inclusive governance is empowering. Structures like HSUP’s project management committee enable co-production and build trust across communities and authorities. Implementers need to be politically savvy – building alliances, anticipating resistance and aligning with both communities’ needs and municipal priorities.

- Institutional anchoring is critical. To survive leadership transitions and changes in personnel, projects need to be embedded in city systems, for instance with dedicated structures such as the proposed Slum Upgrading Unit. Implementers should institutionalise success by embedding new approaches within city departments, with clear mandates and budgets.

- Environmental interventions offer social and economic co-benefits. Greening, solar technology and waste recycling initiatives under HSUP all became sources of income for some community members.

- Flexibility in finance matters. Embedding the HSUFF within the CoH ensured legitimacy and alignment with municipal systems, but also created bureaucratic delays and limited flexibility in fund disbursement and decision making. This experience highlighted that while partnership with local authorities is essential, upgrading funds needs a degree of operational autonomy –, for example, in approving loans or allocating small grants, to respond quickly to community priorities and changing economic realities. Greater autonomy, combined with transparent governance mechanisms, would enhance responsiveness and sustainability in future co-governed financing arrangements.

- Exploring community-based financing as an alternative to conventional banking can offer more accessible funding solutions for infrastructure development, tailoring financial approaches to local contexts.

- Continuity beyond externally catalysed innovations is important. Implementers should plan for sustainability from the onset, to ensure that governance, funding and technical approaches survive beyond initial donor support.

- Implementers should invest in learning and knowledge sharing, for example by creating platforms and spaces for wider learning and reflection.

Participating agencies

Further information

References

Masimba, G and Walnycki, A (2024). “Harare: City report”. ACRC Working Paper 2024-19. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester.

Matamanda, AR (2020). “Battling the informal settlement challenge through sustainable city framework: Experiences and lessons from Harare, Zimbabwe”. Development Southern Africa 37(2): 217-231.

Matamanda, AR, Mafuku, SH and Mangara, F (2020). “Informal settlement upgrading strategies: The Zimbabwean experience”. In: W Leal Filho, A Marisa Azul, L Brandli, P Gökçin Özuyar and T Wall (eds), Sustainable Cities and Communities. Part of the book series, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Cham: Springer, Cham.

Muchadenyika, D (2015). “Slum upgrading and inclusive municipal governance in Harare, Zimbabwe: New perspectives for the urban poor”. Habitat International 48: 1-10.

Muchadenyika, D and Waiswa, J (2018). “Policy, politics and leadership in slum upgrading: A comparative analysis of Harare and Kampala”. Cities 82: 58-67.

Mutsindikwa, NT (2020). Low-income Home Ownership in the Post-colonial City: A Case Study of Harare, Zimbabwe. Doctoral dissertation, University of Zimbabwe.

Acknowledgements

This case study draws on internal DoS/ZHPF documentation from reflection meetings.

The generative AI tool ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025) was used as an assistive resource to support the preparation of this case study. Specifically, it was used to search for and summarise publicly available information relating to the Harare Slum Upgrading Programme; synthesise and organise key details from verified public documents and media reports, which were subsequently cross-referenced by the author; assist in organising information and enhancing readability of complex sections based on materials provided by the authors; and offer suggested formulations, titles and wording options that were subsequently reviewed, verified and edited by the author. All substantive analysis, interpretation, and written content were produced by the author. The text was subsequently reviewed and edited by members of the ACRC database and communications teams prior to publication. Reference: OpenAI (2025) ChatGPT [Large language model]. Available at: https://chat.openai.com (Accessed: 10 September 2025).

Cite this case study as:

Marewo, ME (2025). “Harare Slum Upgrading Program: A community-driven approach to urban reform”. ACRC Urban Reform Database case study. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester.