Key information

Main city: Mzuzu, Malawi.

Scope: City/town level; National level

Lead organisations: Northern Region Water Board

Timeframe: 2010 – ongoing. Start year is approximate.

Themes: Informal settlements; Health; Human rights; Informality; Infrastructure; Water and sanitation

Approaches used in initiative design and implementation:

- Addressing the poverty penalty in informal settlements.

- Enhancing access and affordability of communal water supply.

- Financially sustainable public water provision.

- Recognising urban inequalities in service provision and service quality through differential pricing.

Initiative description

Background and context

National and city context

Since Malawi’s water utilities were commercialised in 1995, regional water boards[1] have struggled to cover the costs of distributing affordable water to a low-income population while maintaining and expanding infrastructure to meet demand (Beard and Mitlin, 2021; Mitlin and Walnyki, 2020). Their efforts at ensuring operational sustainability navigate a context of high-level political interest in keeping tariffs acceptable to consumers, as well as pressure to use revenue for repaying loans from international donors and recovering investment costs (Pihljak et al, 2021).

Mzuzu, Malawi’s third-largest and fastest-growing city, has a municipal population of 250,000, rising to 1.7 million at metropolitan level (GoM, 2019). Over 60% of residents live in informal settlements characterised by density, poverty, poor infrastructure, limited access to basic services and vulnerability to floods and mudslides (Kita, 2017). As in many cities experiencing rapid unplanned urban sprawl, high and increasing demand limits institutional capacity to extend piped water and other infrastructure to meet urban dwellers’ needs. And in low-income areas, the up-front costs of installing piped water to residences are prohibitive to households or infeasible in contexts of insecure tenure. Citizens consequently face challenges securing equitable and affordable access to potable water, with many informal settlement residents relying on combinations of formal, informal, public and private suppliers and other furtive water access pathways (Beard and Mitlin, 2021; Mitlin et al., 2019).

Communal water supply

To cover supply gaps, Mzuzu’s regional utility, the Northern Region Water Board (NRWB), has resorted to providing communal standpipes in informal and low-income areas. These freestanding pipes fitted with a tap are widely used by authorities in African cities (including Malawi’s other major cities of Lilongwe and Blantyre) to provide water to neighbourhoods lacking adequate household-level connections (Acevedo-Guerrero, 2023; Sarkar, 2022; Keener et al., 2010; Gerlach and Franceys, 2010).

Communal standpipes in Malawian cities are managed as fee-charging kiosks by community-based Water Users Associations (WUAs), within a bottom-up, decentralised water management framework that aims to catalyse community participation by empowering citizens to take responsibility for operating and maintaining water systems and ensuring sustainable and equitable distribution of supply (Ferguson and Mulwafu, 2004; Manda, 2019; Holm et al., 2016; Wanda et al., 2012). WUAs are permitted to make a profit as long as surplus is reinvested back into the community. However, such reinvestment often depends on associations’ social commitment to serving their communities. Pihljak et al. (2021), writing about Lilongwe WUAs, highlight the ambiguity and contradictions in associations’ status as, on the one hand, organisations with a social mandate to provide affordable water to communities sustainably for fees reinvested in infrastructure maintenance, cost recovery enhancements and service continuity and, on the other, private profit-making entities often run as a business (Pihljak et al., 2021).

Historically, implementation of communal standpipes in urban Malawi has faced challenges of poor management, lack of clear-cut governance and unsustainability (Chiumya and Gumbo, 2023). Early payment systems faced transparency and accountability issues, with inefficient billing, lack of monitoring and fraudulently adjusted readings contributing to high prices charged to low-income households, further compromising safe water access for vulnerable communities (Holm et al., 2016). WUAs operating in Lilongwe have been found to charge between two and five times the unit price of residential piped water (Water Aid, 2013; Pihljak et al., 2021; Akpabio et al., 2021). There are also gender-related challenges, such as risks for women who have to collect water at night, due to shortages or long queues during the day (Rusca M et al, 2017; Adams et al, 2018; Alda-Vidal et al., 2024).

Wider investment programme

Several larger and smaller projects implemented over the past decade have supported upgrading and expansion of urban water provision in Mzuzu, with financial and technical support from agencies and NGOs, including the European Investment Bank, European Union, Netherlands Enterprise Agency, VEI, UN-Habitat, African Development Bank, Red Cross and Plan International. These (variously) focus on water efficiency and supply coverage, improving service provision in low-income and peri-urban areas, and local authority/utility capacity-strengthening – aiming to improve urban access, affordability and reliability of supply, as well as the utility’s operational and financial sustainability. In one prominent example, a 24.5 million EUR loan from the European Investment Bank supported the NRWB in a 2016-2019 water efficiency project focused on Mzuzu and surrounding areas: constructing intakes, increasing storage capacity of a nearby dam, rehabilitating and upgrading existing water supply systems, increasing water treatment capacities, water demand management to reduce non-revenue water, improving network management, and improving supply to low-income urban areas (EIB, 2016).

Changes in water access

Over time, Mzuzu city’s overall water coverage and reliance on communal supply have both changed. Limited available data shows that between 2012 and 2017, the percentage of residents with access to safe potable water improved from 68% to 95%. Over the same period, the share of households using communal standpoints as their main source of water dropped from 51% to 28% and the proportion accessing water piped to dwellings or private yards increased significantly from 17% to 67%[2] (Wanda et al., 2012; Beard and Mitlin, 2021). Additional water intermittency data cites 2017 average water availability of 20 hours per day, seven days a week (citywide and in one informal settlement, Zolozolo West Ward; Beard and Mitlin, 2021).

[1] Parastatals responsible for the supply of potable water and related services for commercial, industrial, institutional and domestic use (Malawi Water Works Act No. 17 of 1995).

[2] In 2012, most piped water to residences was in formal planned areas and, of the total city population, 17% still accessed water mainly from unprotected wells, 14% from boreholes and 2% from rivers.

Summary of initiative

This case study looks at the implementation and effects of differential water pricing in Mzuzu, which is led by NRWB as part of a nationwide approach to urban areas by all five of Malawi’s regional water boards. It entails setting different tariffs based on mode of access and consumer type and, in particular, offering a relatively lower price per unit for water supplied at communal standpipes compared to water piped to an individual dwelling (Beard and Mitlin, 2021).

The NRWB’s goal was to ensure that, as the water utility, it remained financially sustainable, while expanding water supply to underserved neighbourhoods. In recognising urban inequalities and aiming to improve water affordability for low-income urban dwellers who purchase water from kiosks, differential pricing is an example of how fiscal innovations such as tariff-setting can play a critical role. They can both improve coverage by reducing service provision costs for authorities and enhance access and uptake for marginalised citizens.

Mzuzu’s differential water pricing tariff is one component sitting within a wider programme of investment in urban water infrastructure reforms (see Background and context section above). NRWB has also collaborated with local and international partners that provide financial and technical support to expand and improve water systems and strengthen the capacity of the utility, municipality and community-level WUAs. Mzuzu City Council provided technical assistance and facilitation roles in many of these processes, in which community-based WUAs also participated in addition to their role managing standpipe operations, revenue collection and tariff payments to NRWB.

Customer categories based on mode of access

Differential pricing is implemented using customer categories based on mode of access and consumer type (Table 1). As Mzuzu’s designated water utility, the Northern Region Water Board is the lead agency, mandated to set tariffs, collect revenue and supply water within its jurisdiction (Manda, 2009; Government of Malawi, 2013). Working under a national regulatory framework, water boards develop and implement a tariff structure that prioritises greater affordability for communal standpipe users, offering a lower price per unit for water supplied to standpipes compared to household-level piped systems and commercial water users, in acknowledgement that this source is most commonly used by low-income urban households. Lower tariffs are also set for piped water to a yard (household-level standpipe) rather than inside a dwelling.

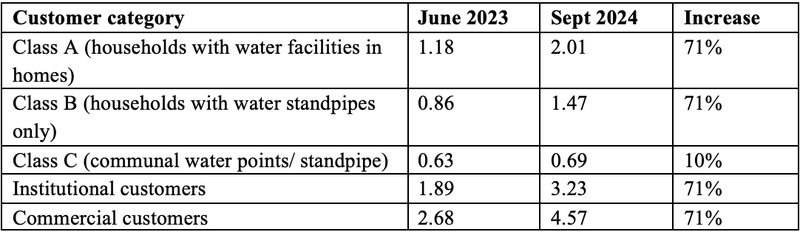

Table 1 displays the latest available data on NRB’s tariffs (last updated in September 2024), at which the standpipe tariff for WUAs stands at 47% of the cost of water piped to yards and 34% of water accessed inside homes. Table 1 also shows that between mid 2023 and mid 2024, the standpipe water tariff was kept relatively low (10% increase) as all others increased significantly (71% increase).

Two-part price-setting process

In the national urban context, differential standpipe water costs to end users are determined through a two-part process. The regional water board, in cooperation with national government, sets an initial bulk tariff (also called integrated block tariff) at which WUAs purchase water from the utility. Within marginal costing methods, this is set at the lowest tariff, limited to the cost of delivering water supply (Coulson et al., 2021). The final cost to users is then established by building in a second tariff that covers kiosk operating costs, which is negotiated between WUAs and the water board (Pihljak et al., 2021; Akpabio et al., 2021). As mentioned above, WUAs can make profits as long as they are (loosely) reinvested in the community.

Malawi’s differential water pricing approach goes a significant way to improving water affordability for low-income households in Mzuzu and elsewhere, reducing the poverty penalty and addressing governance and sustainability challenges described above. However, its implementation is not without ongoing questions as to whether the benefits of the differential system truly trickle down to community members. Challenges exist related to the heterogenous nature of WUAs and the power dynamics involved in setting water prices, such as, for example, determining salaries for kiosk attendants and allocating honoraria for more “importantˮ members’ (Pihljak et al., 2021; Coulson et al, 2021) These are expanded in the Understanding limitations section, below.

[4] Water Services Association of Malawi.

[5] Northern Region Water Board website.

Target population, communities, constituents or "beneficiaries"

The approach to target beneficiaries is consistent with the national framework: low-income urban dwellers, particularly in informal settlements, who lack direct access to residential piped water connections and face challenges affording water provided at communal standpoints/kiosks.

ACRC themes

The following ACRC domains are relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

- Informal settlements (primary domain)

- Health, wellbeing and nutrition

- Neighbourhood and district economic development

Informal settlements: Differential pricing aims at improving water access in informal settlements. This links with the ACRC’s focus on systemic urban challenges, where unaffordable services fail to meet residents’ needs, and there is often need for recognition of different levels of affordability together with service quality. Due to greater reliance on informal or less convenient sources, and despite consuming less water per person, households in informal settlements are often charged a “poverty penaltyˮ, paying more per unit for water and other services than formally planned neighbourhoods. For example, research on water affordability in cities in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America has found households who access water from alternative sources paying up to 52 times the standard rates (Beard and Mitlin, 2021).

In targeting low-income households, the initiative considers historical exclusions from piped water access and applies an equitable pricing approach. Access to affordable water is crucial in enhancing the quality of life in informal settlements (Usuk, 2015) and the initiative supports informal upgrading and stability by ensuring that low-income residents can afford essential services, making informal settlements more liveable without displacing or evicting residents (Ouma et al., 2024).

Health, wellbeing and nutrition: Improving access to clean, affordable water addresses public health needs by reducing reliance on unsafe water sources and lowering the risk of waterborne diseases. Access to adequate, clean water is vital for health and nutrition, particularly in informal settlements, where residents face higher vulnerability to the effects of unsafe water and poor sanitation (Tacoli et al., 2024). Affordability of standpipes also means that more residents will stay away from alternative water sources, such as shallow wells which carry a much higher risk of faecal contamination.

Neighbourhood and district economic development: Reliable and affordable water access facilitates local economic activities, particularly small-scale enterprises that depend on water (Amankwaa, 2017). Reducing the cost burden encourages local economic development in underserved urban neighbourhoods.

The following ACRC crosscutting themes are also relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

Gender

Many gendered inequalities are exacerbated by urban service inadequacies. Due to patriarchal norms, Malawian women and girls in low-income households are often responsible for the unpaid reproductive work of water collection (Adams et al, 2018, Tolhurst et al., 2022; Alda-Vidal et al., 2024). Reducing costs at communal standpipes – in concert with other measures to improve access and supply – eases burdens of time and effort associated with travelling long distances to access affordable water, allowing more time for productive activities, including education and income-generating activities (Dos Santos et al., 2017).

Although there is less information available for Mzuzu, in Lilongwe kiosk attendants are generally women, who get a stable job (relatively unusual in informal settlements) and therefore more livelihood stability (Rusca et al., 2017).

Finance

The initiative aligns with ACRC’s focus on urban public finance by demonstrating how fiscal innovations can support equitable service provision without compromising the financial sustainability of utilities.

Climate change

Informal settlements are highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, due to both high exposure to risks and low capacity to adapt (Dodman et al., 2022). Improving access to affordable, safe water mitigates one of the key impacts of climate change, water insecurity, enhancing low-income urban populations’ climate resilience.

What has been learnt?

Effectiveness/success

How does the initiative define and understand success?

The goals of NRBW’s differential pricing approach were to improve and expand urban residents’ access to safe and affordable water, while contributing to the utility’s financial and operational sustainability. However, this understanding of success can be seen from multiple stakeholder perspectives.

Improved provision and affordability of safe water. For low-income and informal settlement residents, success directly relates to reliable and improved access to safe and affordable safe water, reducing reliance on unsafe water sources, and with related benefits for health and wellbeing. For NRWB, setting tariffs based on mode of access aimed to make public water more affordable to low-income urban dwellers and support the utility’s commitment to expand water services into underserved informal settlements. However, the reliance of standpipe water provision on kiosks run by WUAs raises affordability concerns (expanded below).

Financial sustainability and cost recovery. The NRWB’s goal is to ensure that, as the water utility, it remains financially sustainable while expanding water supply to underserved neighbourhoods. Here, success is tied to the utility’s mandate to provide and expand services without jeopardising its financial capacity to cover all the associated costs. Within the national framework, success sits within broader policy objectives of poverty reduction, equitable service provision and planned urban development.

Understanding of success for this initiative connects with four of the preconditions ACRC identifies as catalysts for urban reform.

- Mobilised citizens pushing for change aligns with community involvement in decisionmaking, particularly tariff setting through WUAs. Where WUAs have active social commitment, these groups of community representatives negotiate for affordable pricing and ensure that community priorities inform tariff setting and other aspects of water provision.

- Formal and informal reform coalitions: implementation was driven by successful stakeholder engagement and collaboration among various actors, including the NRWB, municipal authorities, communities (through WUAs), as well as international funding and technical organisations involved in delivering the wider water infrastructure development strategy.

- Agencies able to build state capacity: core to the initiative is building the water utility’s capacity to expand provision in underserved areas. The initiative's focus on financial sustainability enhances both short-term service delivery and long-term capacity building in water service provision.

- Political commitment from elites: successful implementation relied on the presence of an enabling regulatory environment and the political will of local and national government actors to support equitable access to essential services. The nationally driven differential pricing approach is supported by policymakers, who recognised the importance of pro-poor approaches in reducing urban inequalities.

How successful has the initiative been?

Access to water supply (as well as general coverage through the wider water systems programmes) in Mzuzu city has improved, reaching previously underserved populations and reducing reliance on unsafe water sources (for data on this see Background and context section above). Differential pricing regimes have ensured more inclusive access as more can afford to buy water.

The wider programme within which the initiative sits has fostered capacity building and best practices of community participation in decisionmaking through community engagement, training and the involvement of WUAs in tariff-setting negotiations. This promotes inclusive approaches to development and poverty reduction and strengthens relationships between government and other stakeholders, such as community groups, civil society and international development organisations.

Understanding limitations

Continued inequalities in coverage. City-level data obscures the continued absence of water services in some parts of Mzuzu, and the reliance of those residents on natural water sources. In one informal settlement, Zolozolo West Ward, in 2017, over half of households said they used surface water, groundwater or rain sources for all water uses (Beard and Mitlin, 2021). In the wider context of Malawi’s widespread cost-of-living crisis, affording potable water still remains a challenge for many low-income urban dwellers, where the pre-paid fee-charging kiosk system in place requires them to pay upfront for services or otherwise obtain water from unsafe sources that are relatively cheaper or free. Households who cannot afford kiosk prices often rely on multiple sources of water, practising coping strategies such as reserving safe water for drinking and cooking while using unsafe water sources for other domestic uses (Kusi-Appiah and Mkandawire, 2022; Akpabio et al., 2021).

Continued financial sustainability challenges. The need to balance cost recovery and the human right to water continues to challenge water boards in Malawi. Focusing on Blantyre, Song (2022) raises financial sustainability concerns, finding the calculation and collection of water rates inadequate to match the cost of service, compounded by low willingness to pay water charges among citizens. There is recognition by the NRWB of the need for sensitisation around water supply management, to counter mistrust and negative perceptions among communities related to how water tariffs are calculated (NRWB, 2019).

Kiosk prices and profits. The NRWB’s role in setting a low block tariff for communal standpoints does not guarantee the final cost to domestic users and many kiosk customers still end up paying a higher price for water than those served by in-house connections. Significant disparities exist in the operational costs assumed in the WUAs’ additional tariff, which determines final cost to users, and recent research has shown significant increases in water prices at kiosks and growing profits for these associations (see, for example, Pihljak et al., 2021, on Lilongwe; Akpabio et al., 2021 on Blantyre). While water users’ associations are contractually entitled to make a profit, as long as it is reinvested in the community, the reinvestment often depends on the associations’ commitment to serving their communities. In some cases, the profits are invested in activities that may not be inclusive or empowering, and the benefits of subsidised water from the water utility do not always trickle down to consumers, who pay the costs of WUAs (Rusca et al. 2015). In other cases, new WUAs taking over kiosk operations may inherit historical debts and operate at a deficit, requiring higher tariffs to break even. The risk is therefore that water provision through communal standpipes can be both unaffordable to low-income families and a continued financial burden for water utilities.

Studying WUAs in Blantyre, Coulson (2021) argues that financially sustainable kiosk running costs cannot be born solely by the end user and that reforms are needed: "[t]o reduce WUA costs and the kiosk tariffs, WUAs need more training in financial record keeping and cost management, WUAs should not inherit outstanding kiosk debt upon taking over their operations, and water boards should build kiosk costs over which they have fiscal responsibility into integrated block tariff calculations and subsidize them accordingly" (Coulson 2021:1).

WUA governance and influence. At the local level, social relations and non-market forces also shape how WUAs influence communities’ access to water in urban Malawi (Kusi-Appiah and Mkandawire, 2022). WUAs are not homogeneous across communities, or even among members, with diverse interests and holding inequal influencing powers in water board negotiations. Research in Lilongwe reveals different levels of participation in price-setting, with many WUA steering committees run by local elites with likely conflicts of interest, who are involved in decisionmaking around tariff-setting, while waged employees are only responsible for day-to-day financial and service management (Adams and Boateng, 2018: Adams and Zulu, 2015; Rusca et al., 2015). Ordinary residents do not participate in WUAs’ decisionmaking processes, governance or water board negotiations (Pihljak et al., 2021).

Focus on communal standpipes limits incremental upgrading. The NRWB’s need to balance water affordability with cost recovery leads to periodical increases in tariffs. Although recent changes show a commitment to affordability for low-income users in the deliberate maintaining of low communal standpipe tariffs (see Table 1 above), tariff increases for yard-level standpipes or piped water to homes negatively impact households’ ability to afford the costs of upgrading beyond communal water.

Potential for scaling and replicating

Among similar initiatives outside of Malawi, South Africa made a 2001 policy decision following its 1998 National Water Act No 36 to provide a basic amount of water free of charge to all citizens (Muller, 2008). And the city of Johannesburg has introduced a policy of progressive block tariffs, where households consuming less water (normally low-income urban residents) pay a lower rate, while higher-consumption users (typically wealthier households and businesses) pay higher rates (Dikgang et al., 2019). However, this latter approach only benefits those households with already adequate access to in-house water or yard connections (Burger and Jansen, 2014).

In West Africa, setting low differential water tariffs to improve affordability and access for low-income households has also involved cross-subsidisation, with relatively higher tariffs covering for subsided tariffs to ensure cost recovery and financial sustainability (Menzies, 2016).

Participating agencies

Further information

References

Acevedo-Guerrero, T (2023). “Fifty public-standpipes: Politicians, local elections, and struggles for water in Barranquillaˮ. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 41(1): 165-181.

Adams, Ellis Adjei, Luke Juran, and Idowu Ajibade (2018) “‘Spaces of Exclusion’ in community water governance: a feminist political ecology of gender and participation in Malawi’s urban water user associations." Geoforum 95: 133-142.

Adams, EA and Boateng, GO (2018). “Are urban informal communities capable of co-production? The influence of community–public partnerships on water access in Lilongwe, Malawiˮ. Environment and Urbanization 30(2): 461-480.

Adams, EA and Zulu, LC (2015). “Participants or customers in water governance? Community–public partnerships for peri-urban water supplyˮ. Geoforum 65: 112-124.

Akpabio, E M, Mwathunga, E and Rowan, JS (2021). “Understanding the challenges governing Malawi’s water, sanitation and hygiene sectorˮ. International Journal of Water Resources Development 38(3): 426-446.

Alda-Vidal, C, Browne, AL and Rusca, M (2024). “Gender relations and infrastructural labors at the water kiosks in Lilongwe, Malawiˮ. In Y Truelove and A Sabhlok (eds.), Gendered Infrastructures: Dialectics in Form, Identity and Space. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

Amankwaa, EF (2017). Water and Electricity Access for Home-based Enterprises and Poverty Reduction in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA). PhD thesis, University of Ghana.

Beard, VA and Mitlin, D (2021). “Water access in global South cities: The challenges of intermittency and affordabilityˮ. World Development 147: 105625.

Burger, C and Jansen, A (2014). “Increasing block tariff structures as a water subsidy mechanism in South Africa: An exploratory analysisˮ. Development Southern Africa 31(4): 553-562.

Chiumya, D and Gumbo, J (2023). “Investigating the impact of prepaid meters on communal water points in Malawi: A case study of Lilongwe peri‐urban areas”. World Water Policy 9(4): 929-942.

Coulson, A B, Rivett, M O, Kalin, R M, Fernández, S M, Truslove, J P, Nhlema, M and Maygoya, J (2021). “The cost of a sustainable water supply at network kiosks in Peri-Urban Blantyre, Malawi”. Sustainability 13(9): 4685.

Dikgang J, Murwirapachena G, Mgwele A, Girma H, Simo-Kengne B, Mahabir J, Maboshe M, Kutela D and Mukanjari S (2019). Insight into setting sustainable water tariffs in South Africa. Water Resource Commission. WRC Report. Aug. 2356/1:19.

Dos Santos, S, Adams, EA, Neville, G, Wada, Y, De Sherbinin, A, Bernhardt, EM and Adamo, SB (2017). “Urban growth and water access in sub-Saharan Africa: Progress, challenges, and emerging research directionsˮ. Science of the Total Environment 607: 497-508.

Gerlach, E and Franceys, R (2010). “‘Standpipes and beyond’ – a universal water service dynamicˮ. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association 22(4): 455-469.

Government of Malawi (GoM) (2019). 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census. Zomba: National Statistical Office.

Government of Malawi (2013) Water Resources Act. Lilongwe, Malawi.

Holm, R, Singini, W and Gwayi, S (2016). “Comparative evaluation of the cost of water in northern Malawi: From rural water wells to science educationˮ. Applied Economics 48(47): 4573-4583.

Keener, S, Luengo, M and Banerjee, SG (2010). “Provision of water to the poor in Africa: Experience with water standposts and the informal water sectorˮ. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5387. Available online [pdf] (accessed 1 April 2025).

Kita, S M (2017). “Urban vulnerability, disaster risk reduction and resettlement in Mzuzu city, Malawiˮ. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 22: 158-166.

Kusi-Appiah, A and Mkandawire, P (2022). “Political ecology of household water security among the urban poor in Malawiˮ. Wellbeing, Space and Society 3: 100109.

Manda, MAZ (2019). Understanding the Context of Informality: Urban Planning under Different Land Tenure Systems in Mzuzu City, Malawi. PhD thesis. University of Cape Town.

Menzies, I (2016). Delivering Universal and Sustainable Water Services. Water and Sanitation Program Guidance note. Water and Sanitation Program. World Bank Group.

Mitlin, D, Beard, VA, Satterthwaite, D and Du, J (2019). “Unaffordable and undrinkable: Rethinking urban water access in the global Southˮ. WRI working paper. World Resources Institute. Available online (accessed 1 April 2025).

Mitlin, D and Walnycki, A (2020). “Informality as experimentation: water utilities’ strategies for cost recovery and their consequences for universal access”. The Journal of Development Studies 56(2): 259-277.

Muller, M (2008). “Free basic water – a sustainable instrument for a sustainable future in South Africaˮ. Environment and Urbanization 20(1): 67-87.

NRWB (2019). Malawi NRWB Water Efficiency Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Lunyangwa Dam Raising. Northern Region Water Board. Available online [pdf] (accessed 1 April 2025).

Ouma, S, Beltrame, DC, Mitlin, D and Chitekwe-Biti, B (2024). “Informal settlements: Domain report”. ACRC Working Paper 2024-09. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester. Available online: www.african-cities.org.

Pihljak, LH, Rusca, M, Alda-Vidal, C and Schwartz, K (2021). “Everyday practices in the production of uneven water pricing regimes in Lilongwe, Malawiˮ. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 39(2): 300-317.

Rusca M, Alda-Vidal C, Hordijk M and Kral N (2017). “Bathing without water, and other stories of everyday hygiene practices and risk perception in urban low-income areas: The case of Lilongwe, Malawi”. Environment and Urbanization 29(2): 533-50.

Rusca, M, Schwartz, K, Hadzovic, L and Ahlers, R (2015). “Adapting generic models through bricolage: Elite capture of water users associations in peri-urban Lilongweˮ. The European Journal of Development Research 27: 777-792.

Sarkar, A (2022). “Standpipes, water vendors, and water ATMs: Who wins and who loses?ˮ In A Sarkar, Water Insecurity and Water Governance in Urban Kenya: Policy and Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pages 91-133.

Song, C (2022). “Analysis of the organization, management and operation of Blantyre Water Board in Malawi: Future reforms and perspectivesˮ. Environmental Quality Management 32(2): 287-294.

Usuk, K (2015). Households’ Water Accessibility and Its Influence on their Quality of Life: A Case of Mukuru and Mathare Informal Settlements in Nairobi County. PhD dissertation, University of Nairobi.

Wanda, EM, Gulula, LC and Phiri, G (2012). “An appraisal of public water supply and coverage in Mzuzu City, northern Malawiˮ. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 50: 175-178.

Acknowledgements

Due to the limited availability of information and data specific to Mzuzu, this case study of a city-level initiative within a national framework also draws on research and analysis from the cities of Blantyre and Lilongwe.

Cite this case study as:

Marewo, ME (2025). “Differential pricing to improve water affordability in urban Malawi: The case of Mzuzu”. ACRC Urban Reform Database case study. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester.