Key information

Main city: Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe.

Scope: City/town level; Sub-city level

Lead organisations: Dialogue on Shelter Trust ; Zimbabwe Homeless Peoples’ Federation

Timeframe: 2012 – 2015

Themes: Informal settlements; Health; Informality; Infrastructure; Innovation; Water and sanitation

Main funder agencies: UK Department for International Development (SHARE funder); Municipality of Chinhoyi (financial, in kind); Slum Dwellers International (learning exchanges, core federation support, capacity strengthening); national Gungano urban poor fund (basket fund seeded by various sources including SDI); community contributions (financial, in-kind).

Approaches used in initiative design and implementation:

- Challenging norms and promoting alternative modes of sanitation infrastructure.

- Community-led data collection in informal settlements.

- Leveraging policy provisions and existing relationships with local authorities.

- Participatory action research and knowledge coproduction.

- Scalable, locally specific affordability and financing solutions for sanitation.

Initiative description

Background and context

Around 60% of Zimbabwe’s urban households lack access to basic or safely managed sanitation facilities,[1] with greater deficits in low-income areas. Authorities’ efforts to plan and develop water and sanitation services take place with little involvement of low-income communities, lack data and have a poor understanding of needs, perceptions and coping strategies (Banana et al., 2015a). A clear link can be made between inadequate provision of sanitation (and other services) and limited state capabilities, particularly where services are not provided at scale (Ouma et al., 2024). In many urban contexts, weak or disrupted local governance has resulted in an explosion of informal service provision to address deficiencies (Masimba, 2021), creating parallel systems in both marginalised (informal) and more affluent (formal) settlements. Climate change further exacerbates problems linked to unmet demand for services, challenging efforts towards reliable, equitable service provision.

Fast-growing second tier cities accommodate most urban demographic growth in Africa (Matamanda et al., 2022; ICED, 2017), so their development is crucial. However, they often face additional burdens in financing service provision and infrastructure construction and maintenance (Adelina et al., 2020; Matamanda et al., 2022). In Chinhoyi, provincial capital of Mashonaland West in Zimbabwe, a combination of rapid local growth and national financial constraints has eroded municipal capacity to provide residents with water, sanitation and other basic services (Schwartz et al., 1999; Chinyama and Toma, 2013; Nhapi, 2015). Chinhoyi’s population has doubled since 2002, to 103,000 in 2022 (ZimStat, 2022), driven by natural increase and rural–urban migration linked to widespread loss of employment in surrounding mines and commercial farms.

In 2012, 35% of Chinhoyi’s population (then 80,000) lived without or with inadequate access to improved sanitation, including most of the 44% of municipal residents living in informal settlements (Banana et al., 2015b). Ageing, poorly maintained infrastructure in what were formally planned settlements (peripheral ex-mining towns and more central colonial-era worker hostels) cannot adapt to climate stresses or accommodate the far larger number of families now living there. Many households also face complex and insecure tenure.

Communities lack access to consistent water supplies. There are citywide concerns about maintenance of existing infrastructure and vulnerability to water shortages, with authorities reportedly able to supply only 35% of clean water needs (ZBC News, 2023). Many plots were occupied before bulk infrastructure could be installed and, in 2015, research found that 25% of Chinhoyi’s population lived in areas not connected to the municipal grid (Banana et al., 2015). Other challenges limiting the sustainability of interventions include the city’s centralised, sophisticated wastewater systems, which are expensive to maintain and regularly compromised by power cuts, and the mass exodus of skilled personnel from local authorities since Zimbabwe’s economic crisis started in 2000 (ZHPF and DoS, 2014).

Urban growth highlights the central role of infrastructure in achieving sustainable urbanisation and poverty reduction (ZHPF and DoS, 2016). Meeting sanitation needs in underserved areas can necessitate looking beyond classic individualised, waterborne trunk sewer solutions to seek pragmatic alternatives (Satterthwaite et al., 2015). The urban reform this case study describes took place under the Zimbabwean government’s new Strategy to Accelerate Access to Sanitation and Hygiene (2011-2015) which was developed in the aftermath of a devastating nationwide cholera outbreak linked to urban service deficiencies. This progressive policy prioritised innovative approaches to addressing needs and scaling up existing interventions (ZHPF and DoS, 2014), which meant local authorities were more open to new ideas, including the community-driven data collection and planning, coproduction partnerships, and innovative technology and financing mechanisms described below (Banana et al., 2015).

The initiative documented here took place under the Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research Equity (SHARE) consortium (2010-18), funded by the UK Department of International Development (now FCDO) and led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, with partner organisations International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and Slum Dwellers International (SDI), among others. In Chinhoyi, SHARE built on and amplified earlier collaborative interventions to address urban service deficiencies[2] that had been undertaken by the Zimbabwean SDI Alliance – an SDI-affiliated partnership between Dialogue on Shelter Trust (DoS), a non-governmental organisation, and Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation (ZHPF or Federation), a community-based network working to address service delivery and tenure challenges in Zimbabwean towns and cities.

Parallel SHARE action research projects led by SDI affiliates in Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania allowed for learning and reflection. This built on earlier efforts, notably a visit by the Zimbabwean Alliance to Blantyre, Malawi to learn from projects implementing ecological sanitation (ecosan) technology. The major driver for this learning exchange was Brundish, a 2002-12 greenfield housing project in Chinhoyi, where the Federation was negotiating with the local authority to waive standards and allow for quicker occupation of allocated plots (ZHPF and DoS, 2014). Authority standards stipulated expensive installation of waterborne sewer system infrastructure before occupation. Facing affordability challenges, the Federation negotiated a more incremental approach, allowing them to more gradually mobilise resources for staying on site and to install cheaper and more sustainable technologies to reduce water consumption, such as ecosan. Lessons from Malawi and elsewhere informed development in Brundish and were then picked up by other communities in Chinhoyi, including under SHARE (see below).

SHARE project locations were selected in part due to good existing relationships between SDI groups and local authorities, recognising the critical role of supportive local government for community-centric approaches to citywide sanitation (Banana et al., 2015b). In Chinhoyi, a 2012 Memorandum of Understanding between the Zimbabwean SDI Alliance and municipality had agreed on the importance of community-based responses to Chinhoyi’s housing and service crises and asserted a shared commitment to collaboratively address these issues (Banana et al., 2015a).

[1] That is, living with limited or unimproved access to sanitation facilities, or with open defecation. The comparable figure for across Africa is 48%. “Limited” access is defined as use of improved facilities that miss a “safely managed” criteria and are shared with other households. Source: WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, 2024 (online resource, accessed 27 August 2024).

[2] For example, those documented in Homeless International and Reall (2016) and Masimba (2010).

Summary of initiative

This case study outlines a three-year action research project (2012-15) in Chinhoyi centred on collaboration between local authorities and organised groups of citizens to identify and map sanitation needs in low-income neighbourhoods, and then co-produce appropriate and affordable toilet facilities. Activities were led by the Zimbabwean SDI Alliance. Within SHARE (see above), IIED worked with SDI to conceptualise and manage this action research project.

The initiative is an example of how relations between communities and authorities can be strengthened through knowledge co-production, leading to both tangible improvements and evidence to inform effective policy. By challenging poor relationships between residents and local authorities, it demonstrates the utility that can be brought about by fixing the social contract. It also made some progress in challenging norms by introducing and implementing alternative approaches to sanitation technology, and in demonstrating the value of community contributions to financing and managing sanitation facilities in informal settlements.

Activities were implemented as a collaborative research process between the Zimbabwean SDI Alliance, Municipality of Chinhoyi and Chinhoyi residents, including many who were not Federation members. ZHPF and DoS provided technical support and community mobilisation. The municipality contributed in-kind resources (labour, waiving of fees, technical expertise, land for installing facilities) and mobilised political will by engaging local councillors (Banana et al., 2015). In later stages, resident contributions to constructing facilities were facilitated by loans from ZHPF’s national Gungano urban poor fund [3].

The research approach aimed at understanding dynamics affecting sanitation provision in Chinhoyi through four lenses: (1) affordability, for both residents and local authority; (2) choice of installed technology and its maintenance; (3) local authority capacity beyond financial; and (4) governance and decision making.

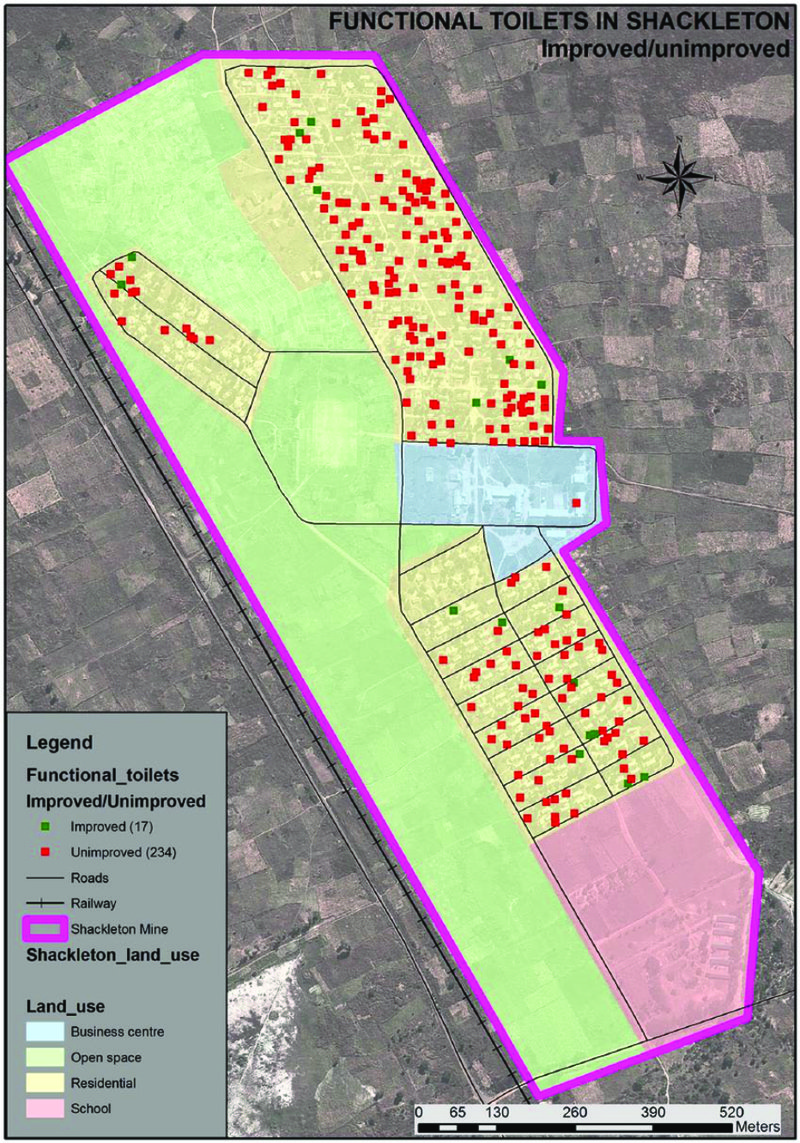

Project design was built around three phases. First, community-led profiling assessed existing provision by collecting data in 11 settlements chosen for the perceived magnitude and nature of their sanitation challenges. This involved GIS mapping existing water and sanitation facilities, such as toilets and boreholes. Local data teams, trained and supported by ZHPF and DoS, worked to develop data tools applied across all settlements, in a collaborative process involving representatives from each settlement as well as local authority planning and engineering professionals.

In the second phase, further data was collected in a smaller number of settlements using focus groups discussions and, where possible, enumerations (socioeconomic household-level surveys). These deepened the understanding of issues of maintenance, affordability, access and distance. Household enumerations and report-back meetings also served as a mobilization tool, enabling mobilization teams to explain the initiative and value of collective action.

Three settlements were then selected for an implementation phase, focused on co-designing and co-constructing solutions that could address immediate needs in a particular location and subsequently be scaled up after testing. Choice of precedent areas was based on extent of service deprivation, the potential for proposed solutions to be scaled up, and community interest in participating. A range of innovative sanitation interventions were developed, together with financing models covering construction and maintenance. Intervention choices were informed by data findings, community preferences and affordability, and considered individual, shared and communal options. This final phase was intended to catalyse longer-term collaborations with the municipality to plan for extending existing sanitation provision and securing more inclusive services.

During the implementation phase, the project successfully adapted interventions to the local economic context and was instrumental in bridging relations between authorities and communities, beyond the direct beneficiaries. This affected perceptions and revenue collection capacity. Its research design effectively tackled typical challenges of community-led upgrading, such as weak community ownership and organisation, absence of holistic thinking in terms of technical interventions, limited financial resources, a lack of will to invest through poor governance, and fragmented links between state institutions and urban dwellers (Mulenga, 2013; see also Learning section below). Crosscutting approaches included community capacity-building, supporting the creation of revolving savings groups, direct community involvement in service delivery, and building better collaborative practices with local authorities.

[3] The Gungano Urban Poor Fund (Shona for “gathering”) was set up by the ZHPF in 1999 and is managed by ZHPF in partnership with DoS. It works by combining collective savings of women-led local savings groups with donor funds to provide loans to secure land tenure, build low-income housing, make incremental improvements to services, and for income generation projects. It is now increasingly used to leverage resources with local authorities to respond to both upgrading needs and climate change impacts.

Target population, communities, constituents or "beneficiaries"

The project targeted low-income Chinhoyi residents living with inadequate access to water and sanitation facilities, including in remote former mining settlements, which, since mine closures after 2000 had experienced administrative overlaps and particularly poor municipal relations.

Interventions designed and delivered in three neighbourhoods are described below. By 2015, these had benefited 308 households (1,700 people) with improved sanitation: 248 with access to shared sanitation facilities between identified households; and 60 with access to improved communal sanitation. The significant ripple effect in Chinhoyi and elsewhere is more difficult to quantify (see Scaling section, below).

In addition to direct beneficiaries, 92 Federation members participated in city sanitation-related events during the project. Three hundred community members (Federation and non-Federation) trained and participated in data collection.

In Shackleton, a remote settlement (2012 population: 4,600 in 540 households), residents lived with high tenure insecurity and social cohesion was low. The project focused on shared toilets, usually between two families and, by 2015, 37 ecosan toilets serving 90 families had been built. Construction was funded through loans of USD 200-350 per toilet, provided as individual loans to two families and repayable over a two-year period at a 1% monthly interest rate. Once 75% of the first loan was repaid, sharing families were eligible for another loan to construct a second toilet.

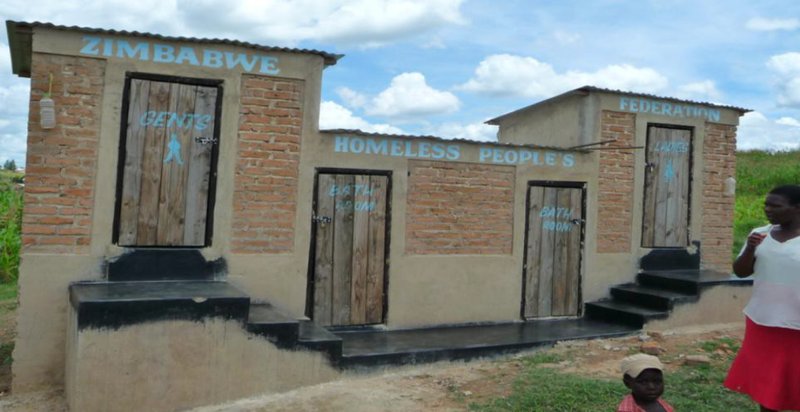

In Gadzema (2012 population: 2,500 people in 700 households), widespread subletting within council rental units complicated issues of ownership and tenure and payment of user charges. The local authority was no longer cleaning and maintaining toilets that it managed, citing poor payment of rates. This led to a blame cycle, in which no party took responsibility for maintenance (Banana and ZHPF, 2015). The Federation supported the community to set up a toilet committee to negotiate with the authority. Project funds were used to construct two new communal toilet blocks serving 60 families (four households sharing a toilet and a bathroom). Cleaning and maintenance responsibilities were transferred from the council to beneficiary households, and the council agreed to a direct budget, derived from rates, to fund further construction of toilet blocks in the settlement, including at a nearby primary school.

In Mpata (2012 population: 5,000 people), the municipality had installed a waterborne sanitation grid in the area. Challenges of individualised tenure and a mix of land-owner residents and tenants with absentee landlords informed community preferences for addressing sanitation needs at the household level. Making solutions affordable was therefore a key concern. The Federation supported the community to set up a sanitation committee to engage with the local authority, and developed a process whereby groups of ten households could access a revolving loan fund to cover construction materials and plumbing. The authority agreed to approval and inspection concessions and to collecting connection fees over a number of payments, rather than up front. By 2015, 25 household-level flush toilets had been constructed in this way.

ACRC themes

The following ACRC domains are relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

- Informal settlements (primary domain)

- Health, wellbeing and nutrition

- Housing

Informal settlements. The initiative centred around knowledge co-creation around water and sanitation issues, particularly access to basic services and identifying inclusive provision of infrastructure in informal settlements, including previously formally planned areas. Collaborative implementation forces behind the initiative, built around the community, emphasised its embeddedness in the domain.

Health, wellbeing and nutrition. The focus on understanding the state of water and sanitation needs in the community helped identify ways in which these could be met and thereby address health and wellbeing.

Housing. Community preferences and decisions for sanitation solutions (such as for communal, shared or individual facilities) as well as the solutions overall feasibility were often informed by the interaction of existing deficiencies in water and sanitation services with local housing arrangements and degree of tenure security in a given settlement context (see targeted population section above).

The following ACRC crosscutting themes are also relevant (links to ACRC domain pages):

Gender

Most leaders and members of the Federation are women, and the SHARE consortium took an approach that was deliberately gender-sensitive and with a generational perspective (Mulenga, 2013; Homeless International and Reall, 2016).

Climate change

Low income urban settlements are particularly at risk from the effects of climate change, including health risks through the contamination of water during flooding and extreme rainfall events. By focusing on upgrading underserviced settlements, the initiative built resilience to adverse climate events through improving access to water and sanitation services for residents of the intervention areas.

What has been learnt?

Effectiveness/success

How does the initiative understand success?

The project set out to: generate knowledge about the sanitation needs and challenges in vulnerable low-income settlements; involve communities in designing, testing, constructing and scaling up sanitation solutions; and demonstrate the potential of bottom-up processes to inform inclusive citywide sanitation strategies. It built on earlier and longer-term efforts. Data collection methodology and research design, including the ways in which interventions were identified and financed, were informed by participatory objectives to capture and address the concerns and preferences of service users and strengthen social capital among communities. A further goal of inclusive urban programming informed the involvement of Chinhoyi municipality, through the project, in areas such as former mining towns that it would not otherwise have worked in.

The Chinhoyi SHARE initiative is an example of the gains that can be drawn from development initiatives that target city systems failures through the participation of those affected, by focusing on provision of basic services in underserved settlements and community-driven design of infrastructure solutions. As such, it overlaps with the following preconditions outlined by the ACRC as catalysts for urban reform:

Mobilised and organised citizens. Project success lay in collective organisation of low-income urban citizens (as data teams, savings groups and sanitation committees), rather than individual endeavours (Tsekleves et al., 2022). The initiative took an integrated approach derived from community-led data collection and participation, built around mobilisation to identify priorities and design responses. It also demonstrates that local governments are often more willing to support local processes if there is a community organisation in place with which they can work (Satterthwaite et al., 2015).

Politically informed and co-produced project design. The initiative leveraged favourable national policy shifts, local authority commitment and positive municipality–civil society relationships, to create new knowledge and co-produce affordable community-led responses to sanitation needs in the absence of more robust state-led interventions.

Reform coalitions. The partnership at the heart of this initiative – between residents, civil society and local authority – showcases successful collaboration across difference. Early in the project, a local steering committee was created to spearhead SHARE efforts in Chinhoyi. The municipality, Federation and DoS identified critical stakeholders, including the local university, church groups and community organisations, then co-hosted a workshop that brought together all groups to collectively set the agenda (that is, introducing and implementing a project that analysed and addressed issues of basic service provision in low-income settlements).

How successful has the initiative been?

Leveraging and strengthening strategic relationships between community groups and local government. The initiative’s collaborative nature strengthened coproduction practices between the Zimbabwean SDI Alliance, community groups and local authorities. At the city level, the project effectively built on existing partnerships between slum dwellers and authorities in Zimbabwe. The centrality of community involvement and leadership to research, data collection and decision making processes (selecting structures and locations where facilities were constructed), all contributed to showcasing the strength of a community-centred and community-led initiative. At settlement level, establishing sanitation committees in each settlement was an important milestone: these led negotiation processes with local councils and played a central role in establishing preferred sanitation propositions.

Driving urban inclusion. The project contributed to driving urban inclusion by working in settlements with contested tenure and land administration arrangements. Alaska and Shackleton, for example, were initially not considered under Chinhoyi municipal jurisdiction. The project helped to catalyse the incorporation process.

Knowledge co-production. Participating in knowledge co-production pushes local authorities to recognise, understand and seek to address the sanitation needs of urban low-income communities. Through processes of community-driven data collection, the initiative improved understanding of the water and sanitation needs of marginalised communities in underserviced parts of a provincial town, as well as associated vulnerabilities, such as insecure tenure.

Addressing sanitation needs. As a direct result of the initiative, households benefited from improved sanitation facilities and service delivery in their areas (Banana et al., 2015a).

Community benefits beyond immediate physical outcomes. Although the initiative responded to state failures, its aims and design meant that implementation and the delivery of objectives were transforming and empowering for communities (McGranahan, 2013) facing broader challenges of weak social cohesion and tenure insecurity. The participatory methodology facilitated a successful grassroots intervention that showcases the capacity of organised groups of low-income residents to improve their communities (Mulenga, 2013). Community groups cultivated problem solving skills and innovation capabilities (Tsekleves et al., 2022), participated actively in organising, financing and managing facilities’ construction, and engaged in wider discussions around the usefulness of the intervention in addressing sanitation concerns in low-income neighbourhoods (SHARE, 2014).

Challenging norms and perceptions. Project partners consider the initiative to have had some success in challenging unhelpful conventions around sanitation technology and governance. Specifically, it improved recognition of the potential of “dry” ecosan technology and of communal, community-managed facilities to meet low-income communities’ long-term sanitation needs. The Chinhoyi activities took place in a national context where local authorities were often not allocating land or allowing communities to occupy allocated plots because these lacked water or sanitation connections. At the same time, costs associated with classic individualised, waterborne sanitation facilities, coupled with insufficient space, were inhibitory to both communities and authorities (despite strong preferences for these). Hence the need to adapt interventions to local economic contexts (Ouma et al., 2024). Against a backdrop of national policy supportive to innovation, and conscious that previous approaches were not working, Chinhoyi’s municipality and settlement communities were, after discussions, willing to consider alternative solutions (Satterthwaite et al., 2015). Ecosan was embraced, with the acknowledgment that unreliable piped water compromises water-based solutions. The project also contributed to shifting local authority policy requiring a single upfront payment for grid connections.

Demonstrating, developing and testing affordable and scalable models. The action research approach allowed participating agencies to test citywide sanitation strategies derived from community-driven solutions, drawing on partners’ expertise and resources to generate knowledge supporting the strength of collaborative research design in water and sanitation (Mulenga, 2013). The approach built on savings-group-orientated incremental loans provided through ZHPF’s revolving urban poor fund, further tailored to each intervention to accommodate inconsistent levels of social capital, varying willingness to participate collectively, and changeable relationships with local government (Banana et al., 2015a).

At the settlement level, financial and technical resources supported communities to experiment with affordable solutions that could meet local needs and act as precedents for other settlements, as well as to establish new ways of relating with local authorities, with lasting results. The general relationship has greatly improved and is producing tangible results. There have been additional concessions as the authority has gained deeper understanding of the capacity of organised low-income communities, including further allocation of plots.

The co-produced sanitation pilots helped bridge relations and enhance understanding by both community and local authority, changing the quality of engagement, shifting from blame to collaboration. For example, utilising the institutional gains and infrastructure learning from the SHARE project, Chinhoyi’s engineering department has since worked with Brundish community in producing water and sewer engineering designs and bills of quantities, as well as supervising the installation of water infrastructure on 256 housing units.

Understanding limitations

“[C]o-production partnerships can serve to empower local groups when there are sufficient political commitment from the state, social capital within the community, and adequate resources available. But this is a tricky equilibrium to maintain, and the unequal advance or presence of each of these elements underpins the uneven yet considerable advances that have been documented in Chinhoyi” (Banana et al., 2015a).

State limitations in Chinhoyi and their effect on service provision underline the structural obstacles underpinning the complexity and magnitude of water and sanitation challenges in secondary African cities. Project partners found that opportunities to capitalise on policy provisions encouraging innovation were at times stymied by accepted norms and negative perceptions of communal and alternative sanitation (Banana et al., 2015a).

Although national strategy promoted innovative and affordable technologies and regulatory restructuring to address urban sanitation deficits, the tendency in Chinhoyi was still to fall back on more familiar approaches – and to see alternative or communal solutions as a stopgap, rather than permanent, scalable solutions. Highly sophisticated bulk infrastructure is still regarded as the “standard” for a city infrastructure system – despite evidence that the systems cannot be maintained, due to their high operational costs amidst increasing poverty, and their reliance on skilled technicians.

The experience in Chinhoyi was also that municipal discomfort can reinforce community resistance to alternative solutions. While communal toilets were clearly more cost-effective, community and local authority perceptions that their construction and management were problematic were backed up by evidence of the poor conditions of communal facilities in the city.

A related challenge is clashes between community preferences and affordability. While many preferred constructing individual toilets, affordability constraints meant decisions were informed by a set of criteria related to convenience and sustainability (McGranahan, 2013). This was compounded by tenure complexities, which influenced motivations to invest in sanitation, and correlated negatively with access, maintenance and management of facilities (Banana et al., 2015). Challenges were addressed through extended discussion between established committees of community members, to eventually reach consensus based on identified and expected benefits.

Delays in formal approval from local authorities limited enumeration activities in some areas, narrowing the scope of the research data generated (McGranahan, 2013).

Potential for scaling and replicating

Since 2015, within the wider context of efforts as above, the initiative’s successes have contributed a ripple effect to efforts to address service provision in informal settlements, within and beyond Chinhoyi.

The achievements have contributed to Chinhoyi becoming a learning centre, particularly in the SDI network, in the application of alternative incremental water and sanitation infrastructure services, as well as in ways of collaborating with local authorities, and in mobilising community resources to co-finance installation costs. Other municipal authorities, including Kadoma, Masvingo, Harare and Chegutu, have all now opened space to partner with communities and pilot new alternatives.

The initiative energised and strengthened the residents’ movement in Chinhoyi, which has subsequently engaged with the municipality around solid waste management, water infrastructure and other service provision in low-income areas, further improving living conditions. Improved relations between communities and municipality also helped address complex governance problems in remote settlements previously excluded from mainstream urban development conversations.

Since SHARE, DoS professionals observe that engagement between communities and the local authority to implement water and sanitation upgrading projects has become more systematic. In some instances, the authority has supported drawing up of plans and designs for water and sanitation infrastructure, and the community has contributed to implementation and procuring materials.

The Chinhoyi efforts have also influenced openness to reform at a national level. Representatives from the National Coordinating Unit and National Action Committee attended the first project meetings and took lessons from the project to the national level (Banana et al., 2015a).

Participating agencies

Further information

References

Homeless International and Reall (2016). “Community-led water delivery for 30,680 slum dwellers and sanitation delivery for 21,520 slum dwellers in Tanzania and Zimbabwe (GPAF-IM.P-099)”. Evaluation Report. Coventry, UK: Homeless International.

ZHPF and DoS (2016). “Water and sanitation bulletin”, June 2016. First edition. Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation, Dialogue on Shelter for the Homeless in Zimbabwe Trust.

Cite this case study as:

Dessie, E, Banana, E and Lines, K (2024). “Chinhoyi action research for inclusive sanitation under the SHARE programme”. ACRC Urban Reform Database case study. Manchester: African Cities Research Consortium, The University of Manchester.